MST124 Unit 6 - Differentiation

Introduction

Calculus allows to work with situations where a quantity is continuously changing and its rate of change isn't necessarily constant.

It applies to all situations where one quantity changes smoothly with respect to another quantity.

Basic calculus splits into

- differential calculus

- integral calculus

1 What is differentiation?

1.1 Graphs of relationships

If a graph that represents the relationship between two quantities is curved, then there's no single gradient value that applies to the whole graph. Instead, the graph has a gradient at each point on the graph.

As with straight-line, the gradient at each point is the rate of change of the quantity on the vertical axis with respect to the quantity on the horizontal axis.

1.2 Gradients of curved graphs

The gradient of straight line is a measure of how steep it is and is calculated as $$ \text{gradient} = \frac{\text{rise}}{\text{run}} $$ Vertical lines don't have gradient. Hence:

Gradient of straight line

The gradient of the straight line through the points $(x_1, y_1)$ and $(x_2, y_2)$, where $x_1 \ne x_2$, is given by $$ \text{gradient} = \frac{\text{rise}}{\text{run}} = \frac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1} $$

A straight-line graph that

- Slopes down from left to right has a negative gradient.

- Is horizontal has a gradient of zero.

- Slopes up from left to right has a positive gradient.

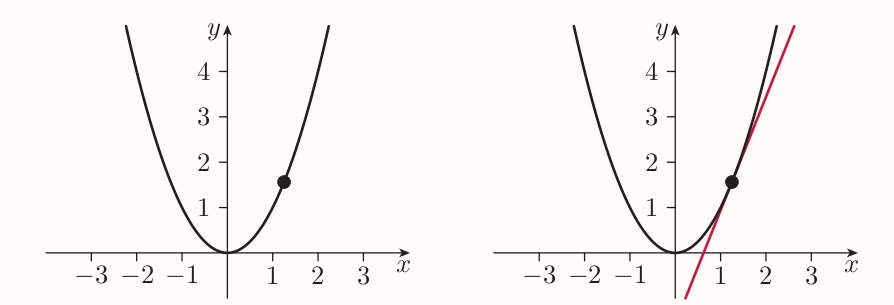

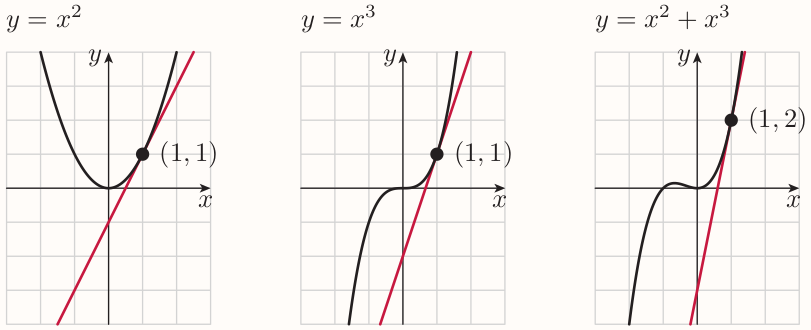

On the other hand curved graphs, as $y = x^2$ don't have a single gradient value. Instead, any particular point on it can be chosen and gradient can be found for the graph at that given point.

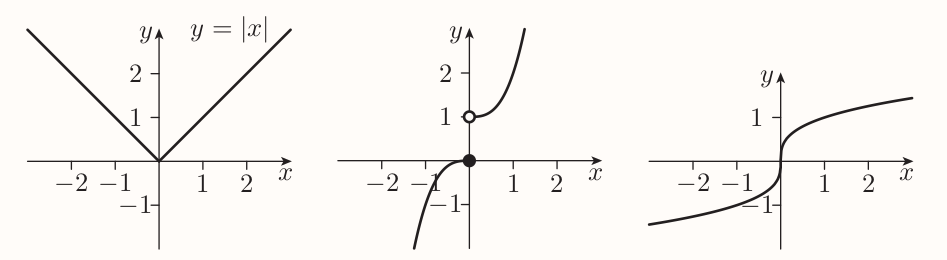

The straight line that 'just touches' the graph at a given point is called the tangent.

The gradient of a graph at a particular point is the gradient of the tangent to the graph at that point.

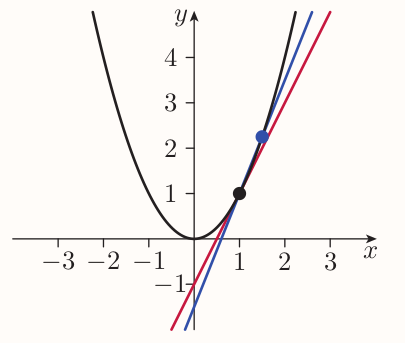

If a graph has a 'sharp corner', like $y = |x|$ then it has no gradient at that point. If a graph has a 'break' at a point (the discontinuity), then the graph has no tangent at that point, hence no gradient. If a graph has a vertical tangent at a point, then the graph has no gradient at it.

1.3 Gradients of the graph of $y = x^2$

$y = x^2$ has a gradient at every point since it has a tangent, which is not vertical, at every point.

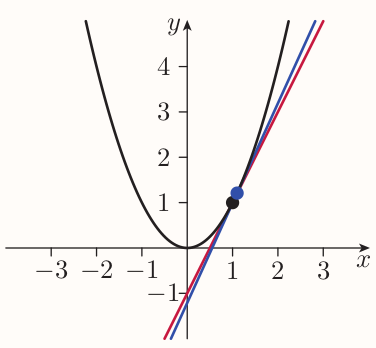

To find a gradient of a point on $y = x^2$ one may start by finding an approximate value by choosing a second point on the graph that is fairly close to first one. Then a gradient of this approximation can be calculated in usual way.

The closer second point is to the first one, the better the approximation is.

E.g. for point $(1, 1)$ and second point $(1.1, 1.21)$, the approximate value for the gradient is $$ \frac{1.21 - 1}{1.1 - 1} = \frac{0.21}{0.1} = 2.1 $$ Second point can lie on both sides of first one.

Following table for $(1, 1)$ and various second points can be devised

| $x$-coord of second point | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.99 | 0.999 | 1.001 | 1.01 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient of line | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.99 | 1.999 | 2.001 | 2.01 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

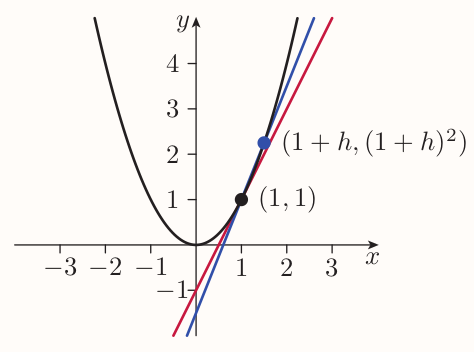

That can be confirmed algebraically as follows. Consider $h$ denoting the increase in the $x$-coordinate from $(1, 1)$ to the second point. The value of $h$ can't be zero. The $x$-coordinate of second point is $1 + h$. The $y$-coordinate of second point is $(1 + h)^2$.

The gradient of the line that passes through both points is

$$ \begin{align*} \text{gradient} &= \frac{(1 + h)^2 - 1}{(1 + h) - 1} \\ &= \frac{1 + 2h + h^2 - 1}{1 + h - 1} \\ &= \frac{2h + h^2}{h} \\ &= \frac{h(2 + h)}{h} \\ &= 2 + h \end{align*} $$

As the value of $h$ gets closer and closer to zero, the gradient of the line $2 + h$ gets closer and closer to 2. Hence the gradient of the graph at $(1, 1)$ must bey exactly 2.

Expressed mathematically as

$2 + h$ tends to $2$ as $h$ tends to $0$

or

the limit of $2 + h$ as $h$ tends to zero is $2$.

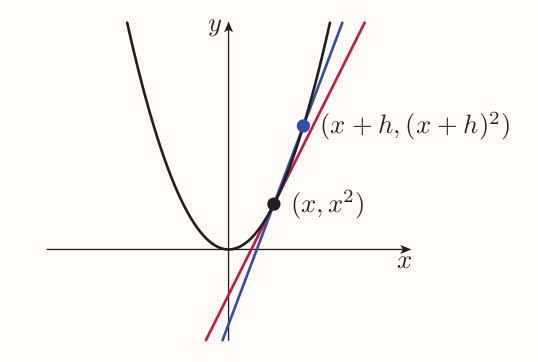

More generic formula can be devised as

$ \begin{align*} \text{gradient} &= \frac{(x + h)^2 - x^2}{(x + h) - x} \\ &= \frac{x^2 + 2xh + h^2 - x^2}{x + h - x} \\ &= \frac{2xh + h^2}{h} \\ &= \frac{h(2x + h)}{h} \\ &= 2x + h \end{align*}$

As the second point gets closer and closer to the original point, the value of $h$ gets closer and closer to $0$ and the gradient gets closer and closer to $2x$. So the gradient of the graph of $y = x^2$ at the point whose $x$-coordinate is denoted by $x$ is given by the formula $$ \text{gradient} = 2x $$

1.4 Derivatives

Consider a function $f$ and input value $x$. The point on the graph of $f$ that corresponds to $x$ is $(x, f(x))$. If the graph of $f$ has a gradient at that point, then we say that $f$ is differentiable at $x$.

It's convenient to think about various gradients of a function $f$ as defining a new function that is related to $f$. The rule of the new function is:

If the input value is $x$, then the output value is the gradient of the graph of $f$ at the point $(x, f(x))$.

This new function is called the derivative (or derived function) of the function $f$ and is denoted by $f'$.

The domain of $f'$ consists of all the values at which $f$ is differentiable.

Differentiation is the process of finding the derivative of a given function $f$.

The value of the derivative of a function $f$ at a particular input value $x$ is called the derivative of $f$ at $x$.

Differentiation from first principle

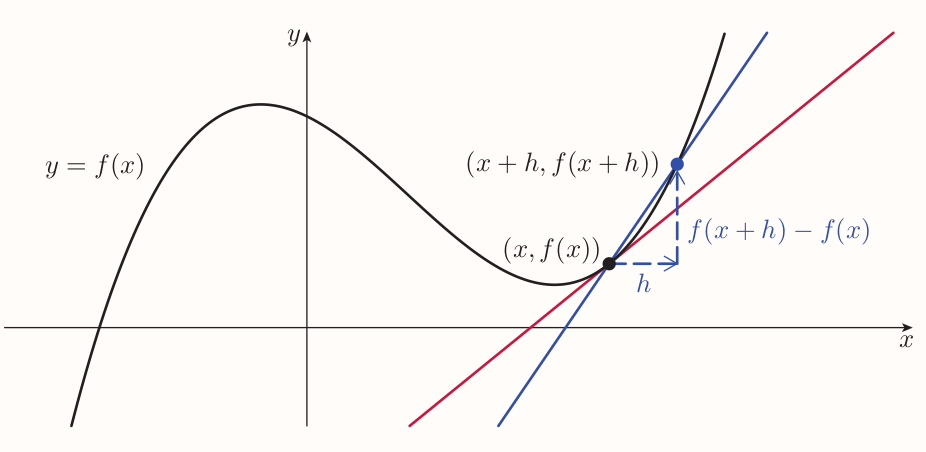

Suppose $f$ and $x$ in the domain of $f$ such that $f$ is differentiable at $x$ (the graph of $f$ has a gradient at $(x, f(x))$). Consider second point with the offset of $h$, then:

The gradient of the line that passes through the two points is given by $$ \text{gradient} = \frac{f(x + h) - f(x)}{(x + h) - x} = \frac{f(x + h) - f(x)}{h} $$ This expression is known as the difference quotient for the function $f$ at the value $x$.

As the value of $h$ gets closer and closer to zero, the value of the difference quotient gets closer and closer to the gradient of the graph at the point $(x, f(x))$, that is $f'(x)$.

To find the formula for $f'(x)$ I need to find, in terms of $x$, the limit of the difference quotient as $h$ tends to zero. In other words, I need to consider what happens to the difference quotient for $f$ at $x$, as $h$ gets closer and closer to zero.

Saying that a function $f$ is differentiable at a particular value of $x$ is the same as saying that the difference quotient for $f$ at $x$ tends to a limit as $h$ tends to zero. It must tend to the same limit for positive values of $h$ as for negative values.

For any function $f$, the derivative $f'$ of $f$ is given by the equation $$ f'(x) = \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{ f(x + h) - f(x) }{ h } $$ for each value of $x$ in the domain of $f$ for which this limit exists.

Leibniz notation

The notation with $f'$ denoting the derivative of a function $f$ is called Lagrange notation or prime notation. Leibniz notation is other extensively used notation.

In general, Lagrange notation is used when thinking in terms of a variable, and a function of this variable. Leibniz notation is used when thinking more of the relationship between two variables.

Consider $y = x^2$, formula for its gradient is $\text{gradient} = 2x$. In Leibniz notation this equation is written as $$ \frac{\text{d}y}{\text{d}x} = 2x $$ Often referred to as the derivative of $y$ with respect to $x$.

It's important to mention that

- The notation is not a fraction

- $\text{d}$ doesn't have any meaning outside of the notation

- $\text{d}$ is not a factor

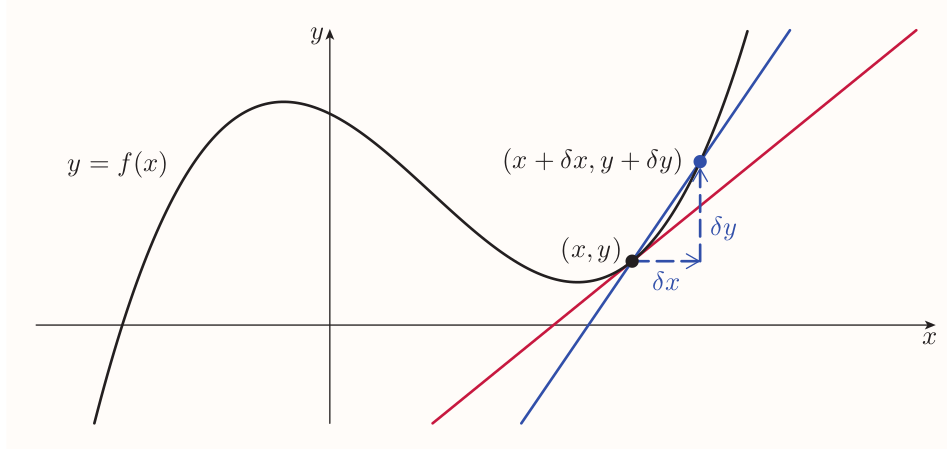

The usefulness of the Leibniz notation can be demonstrated as follows

The emphasis is on the relationship between the variables $x$ and $y$, rather than on the idea of $f$ as a function of $x$. Change in the $x$- and $y$-coordinate is denoted by $\delta x$ and $\delta y$ respectively. $\delta$ (delta) indicates 'a small change in'. So the $x$- and $y$-coordinates of second point are $x + \delta x$ and $y + \delta y$ respectively.

The gradient of the line that passes through he two points is then $$ \frac{\text{rise}}{\text{run}} = \frac{\delta y}{\delta x} $$

The gradient is the limit of $\delta y / \delta x$ as the second point gets closer and closer to the first point.

Functions whose domains include endpoints

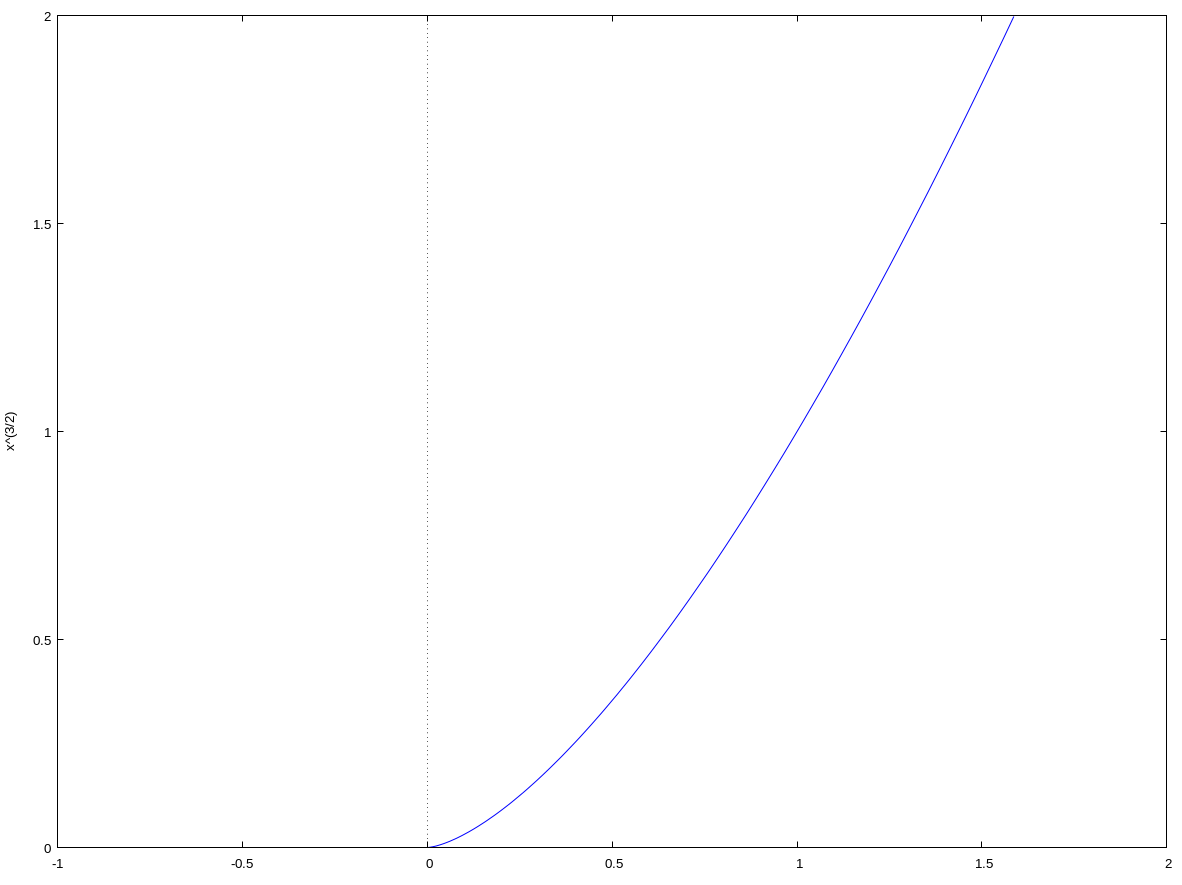

Any function whose domain includes an endpoint isn't differentiable at this endpoint. E.g. $f(x) = x^{3/2}$ has domain $[0, \infty)$:

The endpoint at $0$ (at the origin) can be approached from right but can't from left. Hence the graph doesn't have tangent at the origin, it's not differentiable at $x = 0$. But the graph has a 'gradient on the right' at origin, namely $0$.

So we can say that the function $f(x) = x^{3/2}$ is right-differentiable at $x=0$, and that its right derivative at 0 is 0.

Summary of derivatives

The derivative (or derived function) of a function $f$ is the function $f'$ such that $$ f'(x) = \text{gradient of the graph of } f~ \text{at the point } (x, f(x)) $$ The domain of $f'$ consists of the values in the domain of $f$ at which $f$ is differentiable (that is, the $x$-values that give points at which the gradient exists).

If $y = f(x)$, then $f'(x)$ is also denoted by $\frac{\text{d}y}{\text{d}x}$.

The derivative $f'$ is given by the equation $$ f'(x) = \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{ f(x + h) - f(x) }{ h } $$ The procedure of using this equation to find a formula for the derivative $f'$ is called differentiation from first principles.

2 Finding derivatives of simple functions

2.1 Derivatives of power functions

Any functions of the form $f(x) = x^n$, where $n$ is a real number, is called a power function.

Previously seen formulas for the derivatives of three power functions are: $$ \frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}x}(x^2) = 2x, ~~~ \frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}x}(x^3) = 3x^2, ~~~ \frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}x}(x^4) = 4x^3 $$ They all follow the same pattern:

Derivative of a power function

For any number $n$, $$ \frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}x}(x^n) = nx^{n -1} $$ This formula holds for all values of $n$, including negative and fractional values.

$f(x) = x$ has derivative $f'(x) = 1 \times x^0$; that is$f'(x) = 1$. $f(x) = 1$ (same as $f(x) = x^0$) has derivative $f'(x) = 0$.

2.2 Constant multiple rule

If any graph is scaled vertically by a particular factor, then its gradient at any particular $x$-value is multiplied by this factor.

Scaling a graph by a factor of 3:

Constant multiple rule (Lagrange notation)

If the function $k$ is given by $k(x) = af(x)$, where $f$ is a function and $a$ is a constant, then $$ k'(x) = af'(x) $$ for all values of $x$ at which $f$ is differentiable.

Constant multiple rule (Leibniz notation)

If $y = au$, where $u$ is a function of $x$ and $a$ is a constant, then $$ \frac{ \text{d}y }{ \text{d}x } = a\frac{ \text{d}u }{ \text{d}x } $$ for all values of $x$ at which $u$ is differentiable.

Derivative of a constant function

If $a$ is a constant, then $$ \frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}x}(a) = 0 $$

2.3 Sum rule

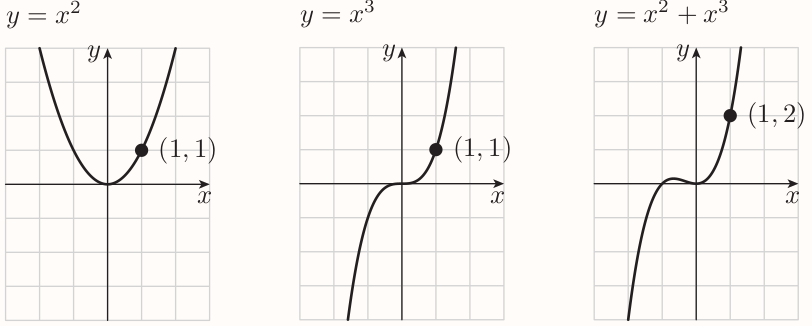

When two functions are added, then the $y$-coordinates of the points on the two graphs are added.

If I add two functions, then the gradient of the sum function at any particular $x$-value is the sum of the gradients of the two original functions at that $x$-value.

E.g.:

Sum rule (Lagrange notation)

If $k(x) = f(x) + g(x)$, where $f$ and $g$ are functions, then $$ k'(x) = f'(x) + g'(x) $$ for all values of $x$ at which both $f$ and $g$ are differentiable.

Sum rule (Leibniz notation)

If $y = u + v$, where $u$ and $v$ are functions of $x$, then $$ \frac{ \text{d}y }{ \text{d}x } = \frac{ \text{d}u }{ \text{d}x } + \frac{ \text{d}v }{ \text{d}x } $$

Every polynomial function (with domain $\mathbb{R}$) is differentiable at every value of $x$.

3 Rates of change

The idea of a gradient as a rate of change applies to curved graphs. However the rate of change is 'instantaneous' value.

Another way to think about the derivative $\text{d}y/\text{d}x$ is that it is the rate of change of $y$ with respect to $x$.

3.1 Displacement and velocity

Relationship between displacement and velocity

Suppose that an object is moving along a straight line. If $t$ is the time that has elapsed since some chosen point in time, $s$ is the displacement of the object from some chosen reference point, and $v$ is the velocity of the object, then $$ v = \frac{\text{d}s}{\text{d}t} $$ (Time, displacement and velocity can be measured in any suitable units, as long as they're consistent).

4 Finding where functions are increasing, decreasing or stationary

Because the derivative of a function gives the gradient at each point on the graph of the function, it gives information about the shape of the graph.

4.1 Increasing/decreasing criterion

Functions increasing or decreasing on an interval

A function $f$ is increasing on the interval $I$ if for all values $x_1$ and $x_2$ in $I$ such that $x_1 < x_2$ $$ f(x_1) < f(x_2) $$ A function $f$ is decreasing on the interval $I$ if for all values $x_1$ and $x_2$ in $I$ such that $x_1 < x_2$ $$ f(x_1) > f(x_2) $$ (The interval $I$ must be part of the domain of $f$.)

Increasing/decreasing criterion

If $f'(x)$ is positive for all $x$ in an interval $I$, then $f$ is increasing on $I$. If $f'(x)$ is negative for all $x$ in an interval $I$, then $f$ is decreasing on $I$.

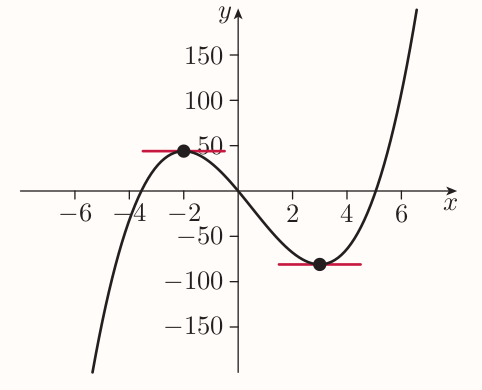

Stationary points

The gradient of $f(x) = 2x^3 - 3x^2 - 36x$ is

- positive on the interval $(-\infty, -2)$

- negative on the interval $(-2, 3)$

- positive on the interval $(3, \infty)$

Between these open intervals, there are points at which the gradient of the graph is zero. Such a point is called a stationary point.

At the left-hand stationary point the value taken by the function is larger than at any other point nearby, hence the function has a local maximum at this point. Similarly the function has a local minimum a the right-hand point.

Turning point is a point where a function has a local maximum or local minimum.

A stationary point of functions as:

when the graph of a functions is constantly decreasing or increasing, is called a horizontal point of inflection.

when the graph of a functions is constantly decreasing or increasing, is called a horizontal point of inflection.

Strategy to fund the stationary points of a function $f$

Solve the equation $f'(x) = 0$

First derivative test (for determining the nature of a stationary point of a function $f$)

If there are open intervals immediately to the left and right of a stationary point such that

- $f'(x)$ is positive on the left interval and negative on the right interval, then the stationary point is a local maximum

- $f'(x)$ is negative on the left interval and positive on the right interval, then the stationary point is a local minimum

- $f'(x)$ is positive on both intervals or negative on both intervals, then the stationary point is a horizontal point of inflection.

Strategy to apply the first derivative test by choosing sample points

- Choose two points (that is, two $x$-values) fairly close to the stationary point, one on each side.

- Check that the function is differentiable at all points between the chosen points and the stationary point, and that there are no other stationary points between the chosen points and the stationary point.

- Find the value of the derivative of the function at the two chosen points.

- If the derivative is positive at the left chosen point and negative at the right chosen point, then the stationary point is a local maximum.

- If the derivative is negative at the left chosen point and positive at the right chosen point, then the stationary point is a local minimum.

- If the derivative is positive at both chosen points or negative at both chosen points, then the stationary point is a horizontal point of inflection.

4.3 Uses of finding stationary points

Properties of graphs of cubic functions

The graph of every cubic function has the following properties.

- There are two, one or no stationary points

- Apart from at any stationary points and in the interval between them if there are two,

- the graph slopes up from left to right if the coefficient of $x^3$ in the rule of the function is positive

- the graph slopes down from left to right if the coefficient of $x^3$ is negative.

- If there are two stationary points, then one is a local maximum and the other is a local minimum, and the graph slopes the other way in the interval between them.

- If there is one stationary point, then it is a horizontal point of inflection.

- There are three, two or one $x$-intercepts.

- There is one $y$-intercept.

- The graph tends to plus or minus infinity for large positive and large negative values of $x$.

Finding the greatest and least values of a function an interval of the form $[a, b]$

(This strategy is valid when the function is continuous on the interval, and differentiable at all values in the interval except possibly the endpoints.)

- Find the stationary points of the function.

- Find the values of the function at any stationary points inside the interval, and at the endpoints of the interval.

- Find the greatest or least of the function values found.

5 Differentiating twice

5.1 Second derivative

The derivative of a function is itself a function, sometimes called the derived function. Meaning it can itself be differentiable. The second derivative (or second derived function) is the function that is obtained by differentiating a function twice.

In Lagrange notation, the second derivative of a function $f$ is denoted by $f''$.

In Leibniz notation, the second derivative of $y$ with respect to $x$ is denoted by: $$ \frac{d^2y}{dx^2} $$ With following reasoning: The second derivative can be written as $$ \frac{d}{dx}(\frac{d}{dx}y) $$ Which was historically abbreviated as $$ (\frac{d}{dx})^2y~,\text{and then to}~~ \frac{d^2y}{dx^2} $$

The domain of the second derivative of a function consists of all the values of $x$ at which its first derivative is differentiable. It's said that the original function is twice-differentiable at such values of $x$.

Third, forth, Nth derivative can be taken in same way.

The derivative of a function is sometimes called its first derivative. Hence the word 'first' in 'first derivative test'.

Derivative of a function tells the gradient of the graph of the function. So the second derivative tells the gradient of the graph of the first derivative. Hence the second derivative also gives an information about the shape of the graph of the original function.

E.g. suppose an interval on which the second derivative of a particular function is positive. By the increasing/decreasing criterion, this means that the first derivative is increasing on that interval. In other words, the gradient of the graph of the original function is increasing on that interval.

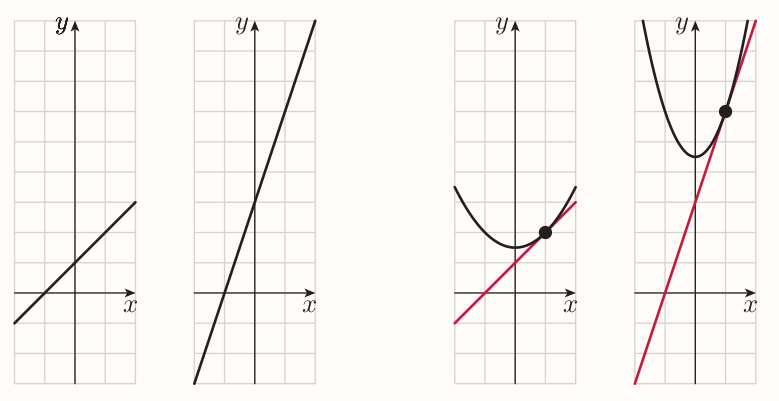

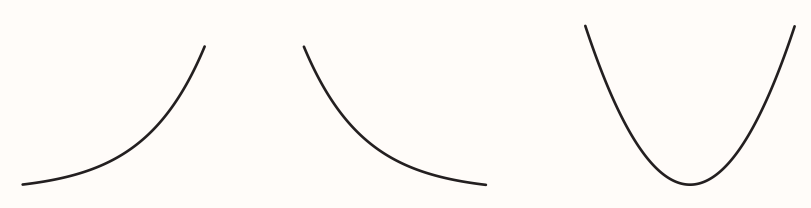

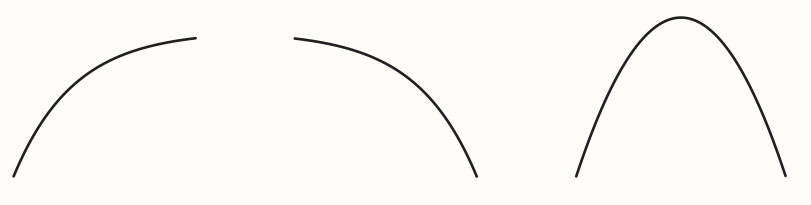

Meaning that the shape of the graph of the original function on the interval must be something like:

All of these are sections of the graphs with increasing gradient.

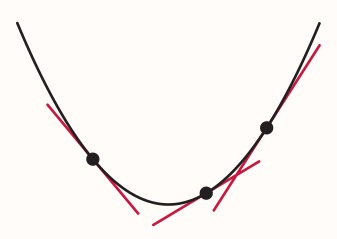

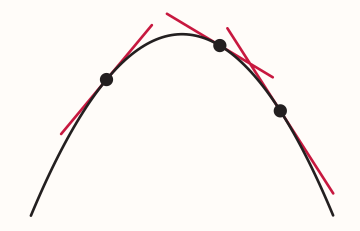

A section of a graph shaped like one of the diagrams above is said to be concave up. A graph is concave up on an interval if the tangents to the graph on that interval lie below the graph:

When there is an interval on which the second derivative of a particular function is negative then, by the increasing/decreasing criterion, the first derivative is decreasing on that interval. Meaning the shape of the graph of the original function on the interval must be something like:

A section of a graph shaped like this is said to be concave down. A graph is concave down on an interval if the tangents to the graph on that interval lie above the graph:

Sometimes, the words convex and concave are used instead of concave up and concave down, respectively.

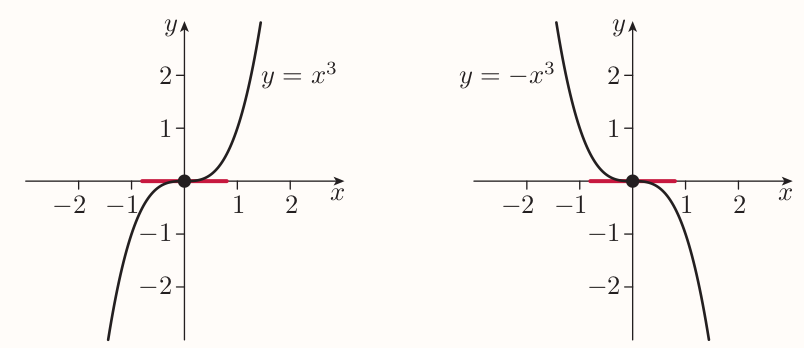

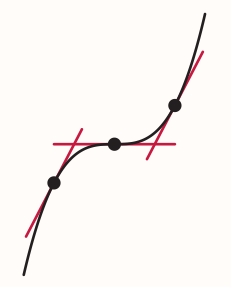

A point where a graph changes from concave up to concave down or vice versa is called a point of inflection. E.g. $f(x) = x^3$ has a point of inflection at the origin:

If the gradient of a graph at a point of inflection is zero, then the point is a horizontal point of inflection. Otherwise the point is a slant point of inflection.

Concave up/concave down criterion

If $f''(x)$ is positive for all $x$ in an interval $I$, then $f$ is concave up on $I$. If $f''(x)$ is negative for all $x$ in an interval $I$, then $f$ is concave down on $I$.

Second derivative test (for determining the nature of a stationary point)

If, at a stationary point of a function, the value of the second derivative of the function is

- negative, then the stationary point is a local maximum

- positive, then the stationary point is a local minimum

When the value of the second derivative at a stationary point is zero then I can't use the second derivative test to determine the nature of the stationary point.

5.2 Rates of change of rates of change

Relationship between displacement, velocity and acceleration

Suppose that an object is moving in a straight line. If $t$ is the time that has elapsed since some chosen point in time, and $s$, $v$ and $a$ are the displacement, velocity and acceleration of the object, respectively, then $$ v = \frac{\text{d}s}{\text{d}t}, ~~ a = \frac{\text{d}v}{\text{d}t}, ~~ a = \frac{\text{d}^2s}{\text{d}t^2} $$