MST124 Unit 5 - Coordinate geometry and vectors

Introduction

Coordinate geometry is an area of mathematics where equations and coordinates of points are used to investigate geometric problems.

1 Distance

1.1 The distance between two points in the plane

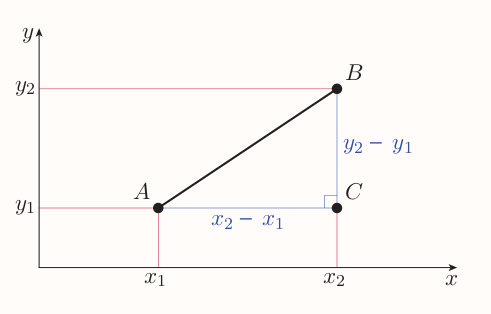

For any points $A(x_1, y_1)$ and $B(x_2, y_2)$ a right angled triangle can be constructed:

So by Pythagoras' theorem the distance between $A$ and $B$ is $$ \sqrt{(x_2 - x_1)^2 + (y_2 - y_1)^2} $$

The formula holds for any position of $A$ and $B$.

1.2 Midpoints and perpendicular bisectors

Locus of points is a collection of all points that satisfy a particular property (e.g. $y = 2x$).

Equidistant points are such points that have same distance from set of other points.

All the points that are equidistant from two particular points form a line that is perpendicular to the line passing through the original two points.

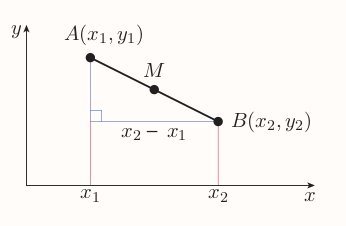

In order to find an equation of such a line the midpoint has to be identified

$x$-coordinate of $M$ is equal to $x$-coordinate of $A$ plus half of the run from $A$ to $B$, hence $$ x_1 + \frac{x_2 - x_1}{2} = \frac{2x_1 + x_2 - x_1}{2} = \frac{x_1 + x_2}{2} $$

Sample applies to $y$-coordinate, giving

Midpoint formula

The midpoint of the line segment joining the points $(x_1, y_1)$ and $(x_2, y_2)$ is $$ (\frac{x_1 + x_2}{2}, \frac{y_1 + y_2}{2}) $$

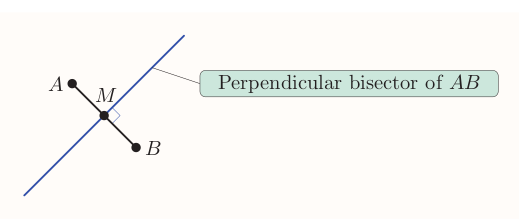

Perpendicular bisector is a line that passes through some other line to which is perpendicular and divides it to two equal parts.

Product of gradients of two lines that are perpendicular and not parallel to the axes is $-1$, so the gradient of perpendicular bisector of $AB$ is $$ \frac{-1}{\text{gradient of}~ AB} $$

Finding a perpendicular bisector

- Find the midpoint

- Find the gradient of the line segment using $(y_2 - y_1) / (x_2 - x_1)$.

- Find the gradient of the perpendicular bisector using $-1/XY$

- Find the equation of the perpendicular bisector using the fact that the line with gradient $m$ passing through the point $(x_1, y_1)$ has equation $y - y_1 = m(x - x_1)$

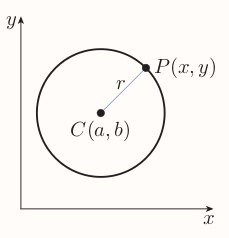

Circles

can be defined as the locus of points that are at a particular distance from a specific point. The specified point is the centre of the circle, and the distance is the radius.

2.1 The equation of a circle

By the distance formula, every point $(x, y)$ on the circle satisfies the equation

$$

\sqrt{(x - a)^2 + (y - b)^2} = r

$$

giving the

By the distance formula, every point $(x, y)$ on the circle satisfies the equation

$$

\sqrt{(x - a)^2 + (y - b)^2} = r

$$

giving the

Standard form of the equation of a circle

The circle with centre $(a, b)$ and radius $r$ has equation $$ (x - a)^2 + (y - b)^2 = r^2 ~~~(1) $$

An equation of any circle can be written as an equation with terms in $x^2$, $y^2$, $x$ and $y$ and a constant term. But not every equation of this form is the equation of a circle, not all such equation can be rearranged to standard form.

Any equation with terms in which $x^2$ and $y^2$ have different coefficients is not the equation of the circle as when $(1)$ is multiplied out those coefficients are always 1.

An equation like $(x - 2)^2 + (y + 1)^2 = -4$ is not an equation of a circle as no point $(x, y)$ satisfies it as the square of every real number is non-negative.

Similarly equation like $(x - 5)^2 + (y - 3)^2 = 0$ is satisfied only by single point $(5, 3)$, hence is not an equation of circle.

Equations like $x^2 + 2y^2 = 4$ represent an ellipse and equations like $x^2 - 2y^2 = 4$ hyperbola.

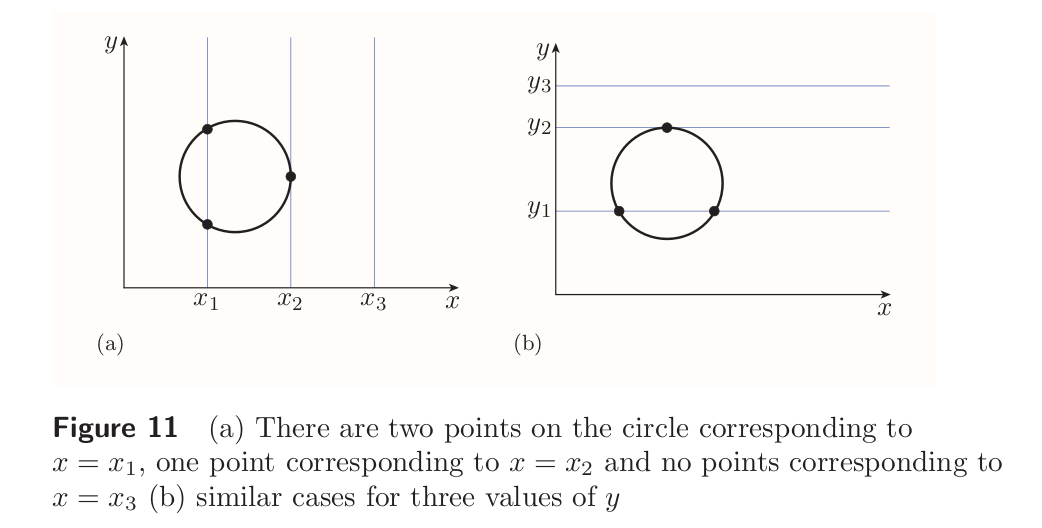

Finding a point on circle is straightforward only when one of the coordinates is known, then it can be substituted to the equation leading to solvable quadratic equation. The equation can have two, one or no solution as usual.

The equation of a circle like $(x - 1)^2 + (y - 5)^2 = 9$ is said to be in implicit form as it doesn't express either of two variables in terms of the other.

Equation as $y = 3x^2 + 2$ is in explicit form, it expresses the variable $y$ as a function of $x$. The equation of a circle can't be written in explicit form. The equation of a circle can be rearranged as follows $$ \begin{align} (x - 1)^2 + (y - 5)^2 &= 9 \ (y - 5)^2 &= 9 - (x - 1)^2 \ y - 5 &= \pm \sqrt{9 - (x - 1)^2} \ y &= 5 \pm \sqrt{9 - (x - 1)^2} \end{align} $$ Such equation doesn't express $y$ as a function of $x$ since each value of $x$ gives two values of $y$ due to $\pm$.

2.2 The circle through three points

A single straight line can be defined with two points, that's not true for circles, many of different circles can pass through two chosen points.

However when three points are chosen, then as long as those don't lie on straight line, there is only one circle that passes through all three points.

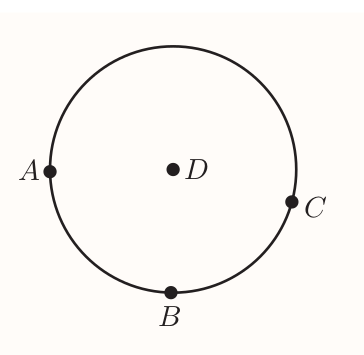

To find the equation of the circle that passes through three points consider:

Once $D$ is found then it's straightforward to get the radius.

$D$ is equidistant from $A$, $B$ and $C$.

In particular it's equidistant from $A$ and $B$ hence it lies on the perpendicular bisector of $AB$. Same applies for $B$ and $C$.

Hence $D$ is a point at which the two perpendicular bisectors intersect.

Once $D$ is found then it's straightforward to get the radius.

$D$ is equidistant from $A$, $B$ and $C$.

In particular it's equidistant from $A$ and $B$ hence it lies on the perpendicular bisector of $AB$. Same applies for $B$ and $C$.

Hence $D$ is a point at which the two perpendicular bisectors intersect.

Strategy to find the equation of the circle passing through three points

- Find the equation of the perpendicular bisector of the line segment that joins any pair of the three points.

- Find the equation of the perpendicular bisector of the line segment that joins a different pair of the three points.

- Find the point of intersection of these two lines. This is the centre of the circle.

- Find the radius of the circle, which is the distance from the centre to any of the three points.

Hence write down the equation of the circle.

3 Points of intersection

3.1 Points of intersection of a line and a curve

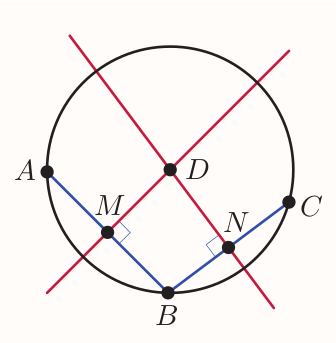

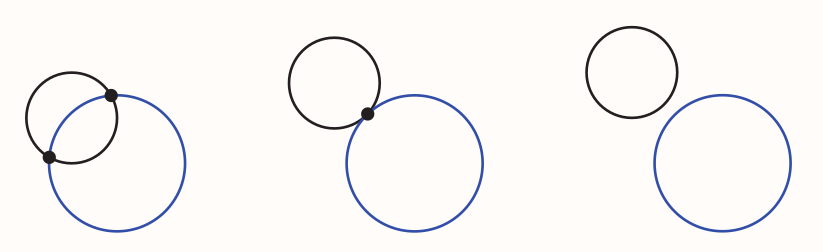

A line and a circle can have two, one or no points of intersection.

The points of intersection can be found by solving the equation of the line and the equation of the circle simultaneously. Leading to a quadratic equation.

Same can be done with straight line and parabola.

3.2 Points of intersection of two circles

Two circles may intersect at two points, one point or not at all.

Such points can be found by solving the equations of both circles simultaneously. That can be done via eliminating the terms in $x^2$ and $y^2$ by subtracting one equation from the other. Leading to a linear equation representing the straight line passing through the points of intersection. Next apply the steps from 3.1.

4 Working in three dimensions

4.1 Three-dimensional coordinates

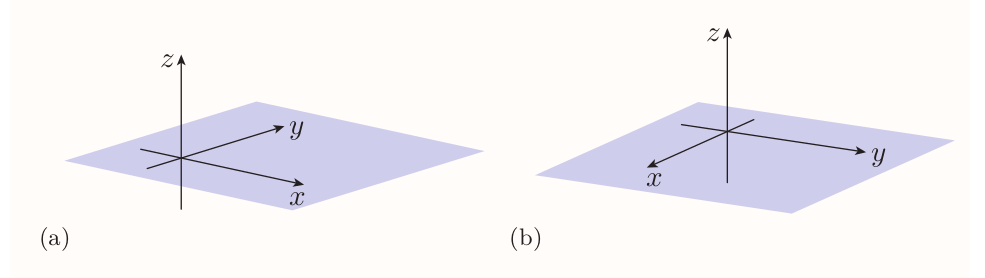

Are obtained by extending the two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system by a third axis, the $z$-axis, at right angles to the $x$- and $y$-axes.

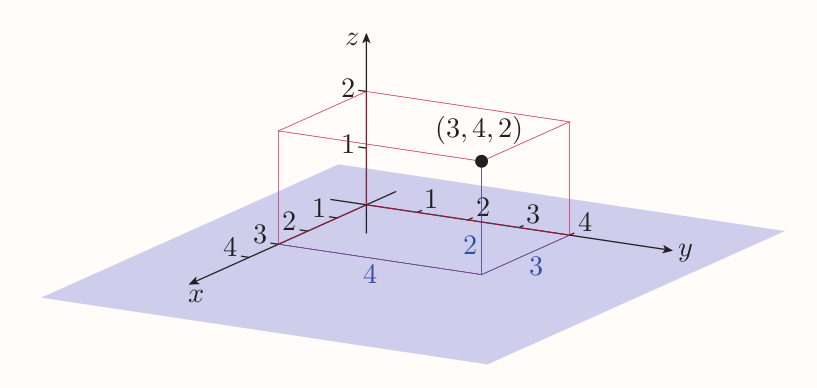

$x, y$-plane, $x, z$-plane and $y, z$-plane are known as the coordinate planes. The positive direction of the $z$-axis is called the positive $z$-direction (similar terminology applies to other axes). The position of a point in three dimensions is specified as the triple $(x, y, z)$.

4.2 The distance between two points in three dimensions

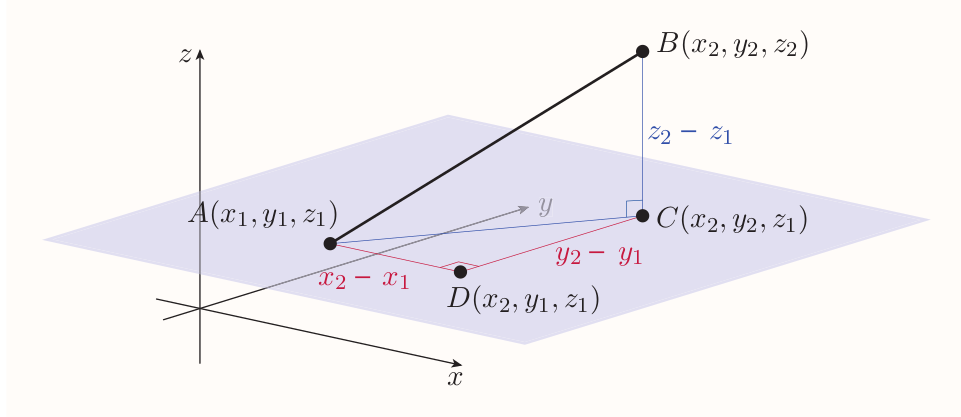

Considering $A(x_1, y_1, z_1)$ and $B(x_2, y_2, z_2)$ as follows:

The distance $AB$ is the length of the hypotenuse of the right-angled triangle with vertices $A$, $B$ and $C$, hence $$ AB^2 = AC^2 + BC^2 ~~~(2) $$ where $AC$ is given by $$ AC^2 = AD^2 + DC^2 $$ That can be substituted to (2) $$ AB^2 = AD^2 + DC^2 + BC^2 $$ Since

- $AD = x_2 - x_1$

- $DC = y_2 - y_1$

- $BC = z_2 - z_1$

the equation is $$ AB^2 = (x_2 - x_1)^2 + (y_2 - y_1)^2 + (z_2 - z_1)^2 $$ As with the distance formula in two dimensions this equation holds no matter where the points $A$ and $B$ lie.

Distance formula (three dimensions)

The distance between two points $(x_1, y_1, z_1$ and $(x_2, y_2, z_2)$ is $$ \sqrt{(x_2 - x_1)^2 + (y_2 - y_1)^2 + (z_2 - z_1)^2} $$

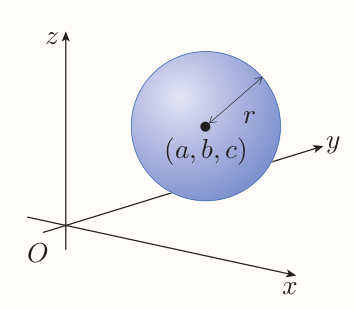

4.3 The equation of a sphere

In three dimensions, the locus of points equidistant from a particular point is a sphere.

The radius of the sphere is the distance between its center and a point on it, hence

The standard form of the equation of a sphere

The sphere with centre $(a, b, c)$ and radius $r$ has equation $$ (x - a)^2 + (y - b)^2 + (z - c)^2 = r^2 $$

5 Vectors

5.1 What is a vector?

Some mathematical quantities need to be specified using a size and a direction. Displacement is the position of one point relative to another specified by distance and direction. Velocity is speed together with direction. Such quantities are called vectors. Magnitude is the size of a vector.

Quantities that have size but no direction are called scalars.

A vector with non-zero magnitude can be represented by an arrow.

Once a scale is defined, any two arrows with same direction and length represent the same vector.

Vectors are represented as

- bold lowercase letter in typed texts - $\textbf{v}$

- underlined lowercase letter in written texts - $\underline{v}$

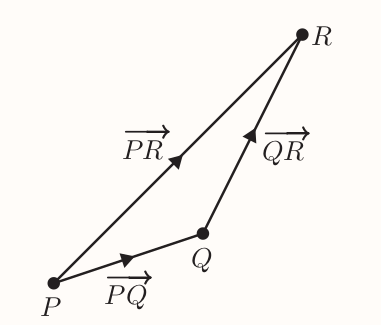

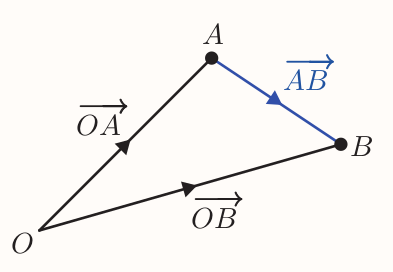

Displacement vectors are denoted as e.g. $\overrightarrow{PQ}$

The magnitude of a vector $\textbf{v}$ is scalar denoted by $|\textbf{v}|$. It's read as 'the magnitude of v', 'the modulus of v' or 'mod v'.

It applies that $PQ = |\overrightarrow{PQ}|$.

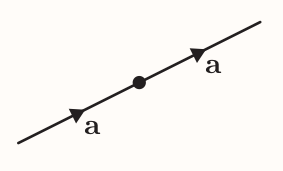

Equal vectors

Two vectors are equal if they have the same magnitude and the same direction.

The zero vector

The zero vector is denoted by $\textbf{0}$ (bold zero), is the vector whose magnitude is zero. It has no direction.

Addition of vectors

The method of combining two vectors to produce another vector is called vector addition, e.g. $\vec{PQ} + \vec{QR} = \vec{PR}$

Triangle law for vector addition

To find the sum of two vectors $\textbf{a}$ and $\textbf{b}$, place the tail of $\textbf{b}$ at the tip of $\textbf{a}$. Then $\textbf{a} + \textbf{b}$ is the vector from the tail of $\textbf{a}$ to the tip of $\textbf{b}$.

The sum of two vectors is also called their resultant vector.

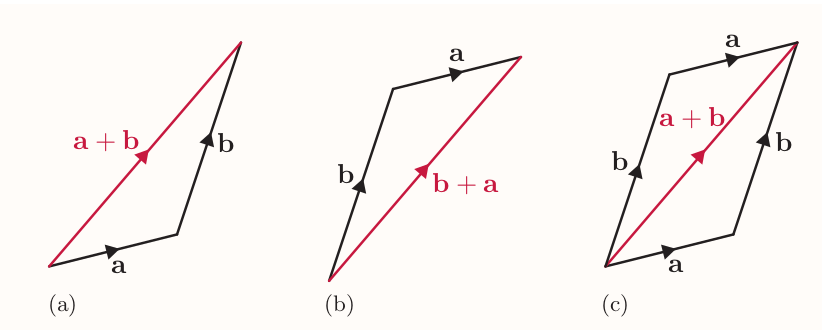

The order of operations doesn't matter since:

Parallelogram law for vector addition

To find the sum of two vectors $\textbf{a}$ and $\textbf{b}$, place their tails together, and complete the resulting figure to form a parallelogram. Then $\textbf{a}$ + $\textbf{b}$ is the vector formed by the diagonal of the parallelogram, starting from the point where the tails of $\textbf{a}$ and $\textbf{b}$ meet.

More than two vectors can be added by placing them all tip to tail.

Addition of zero vector leaves original vector unchanged $\textbf{a} + \textbf{0} = \textbf{a}$.

It's not possible to add a scalar to a vector.

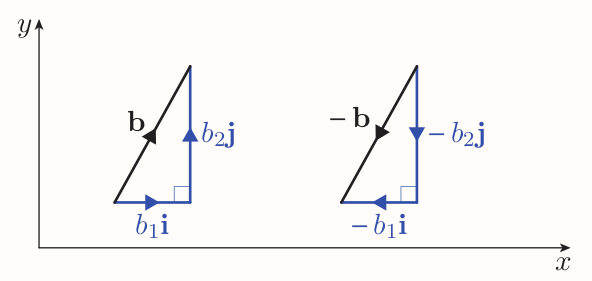

Negative of a vector

The negative of a vector $\textbf{a}$, denoted by $-\textbf{a}$, is the vector with the same magnitude as $\textbf{a}$, but the opposite direction.

For any points $P$ and $Q$, the position vectors $\vec{PQ}$ and $\vec{QP}$ have the property that $-\vec{PQ} = \vec{QP}$.

For any vector $\textbf{a}$ and its negative $-\textbf{a}$ it applies that $\textbf{a} + (-\textbf{a}) = \textbf{0}$.

Subtraction of vectors

To subtract $\textbf{b}$ from $\textbf{a}$, add $-\textbf{b}$ to $\textbf{a}$. That is $$ \textbf{a} - \textbf{b} = \textbf{a} + (-\textbf{b}) $$

For any vector $\textbf{a}$, $\textbf{a} - \textbf{a} = \textbf{0}.$

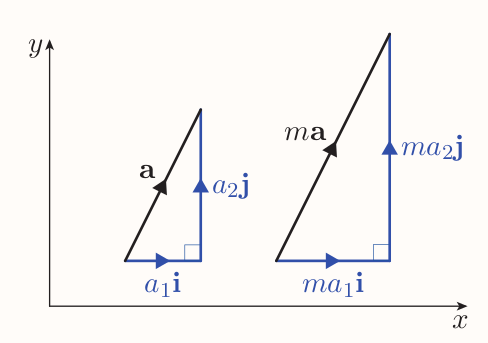

Multiplication of vectors by scalars

When vector $\textbf{a}$ is added to itself the resultant vector $\textbf{a} + \textbf{a}$ has the same direction as $\textbf{a}$ but twice the magnitude. It's denoted by $2\textbf{a}$ and its said to be a scalar multiple of the vector $\textbf{a}$.

Scalar multiple of a vector

Suppose that $\textbf{a}$ is a vector. Then, for any non-zero real number $m$, the scalar multiple $m\textbf{a}$ of $\textbf{a}$ is the vector

- whose magnitude is $|m|$ times the magnitude of $\textbf{a}$

- that has the same direction as $\textbf{a}$ if $m$ is positive, and the opposite direction if $m$ is negative.

Also, $0\textbf{a} = \textbf{0}$. (That is, the number zero times the vector $\textbf{a}$ is the zero vector.)

5.2 Vector algebra

Properties of vector algebra

The following properties hold for all vectors $\textbf{a}$, $\textbf{b}$ and $\textbf{c}$, and all scalars $m$ and $n$.

- $\textbf{a} + \textbf{b} = \textbf{b} + \textbf{a}$

- The vector addition is commutative

- $(\textbf{a} + \textbf{b}) + \textbf{c} = \textbf{a} + (\textbf{b} + \textbf{c})$

- The vector addition is associative

- $\textbf{a} + \textbf{0} = \textbf{a}$

- $\textbf{a} + (-\textbf{a}) = \textbf{0}$

- $m(\textbf{a} + \textbf{b}) = m\textbf{a} + m\textbf{b}$

- The scalar multiplication is distributive over the addition of vectors.

- $(m + n)\textbf{a} = m\textbf{a} + n\textbf{a}$

- The scalar multiplication is distributive over the addition of scalars.

- $m(n\textbf{a}) = (mn)\textbf{a}$

- $1\textbf{a} = \textbf{a}$

Multiplication of vector by another vector will be explored later on. Division of a vector by another vector is not possible.

5.3 Using vectors

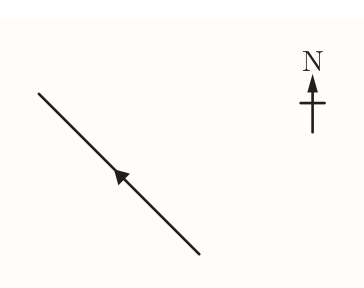

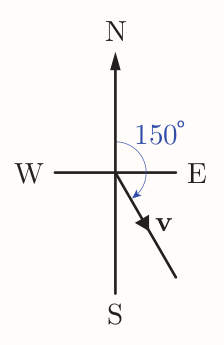

A bearing is an angle between $0^{\circ}$ and $360^{\circ}$, measured clockwise in degrees from north to the direction of interest.

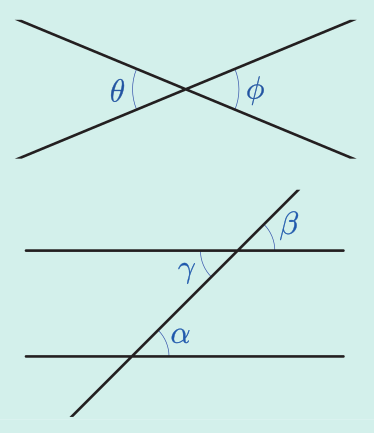

Opposite, corresponding and alternate angles

Where two lines intersect opposite angles are equal

Where a line intersects parallel lines corresponding angles are equal and alternate angles are equal.

6 Component form of a vector

6.1 Representing vectors using components

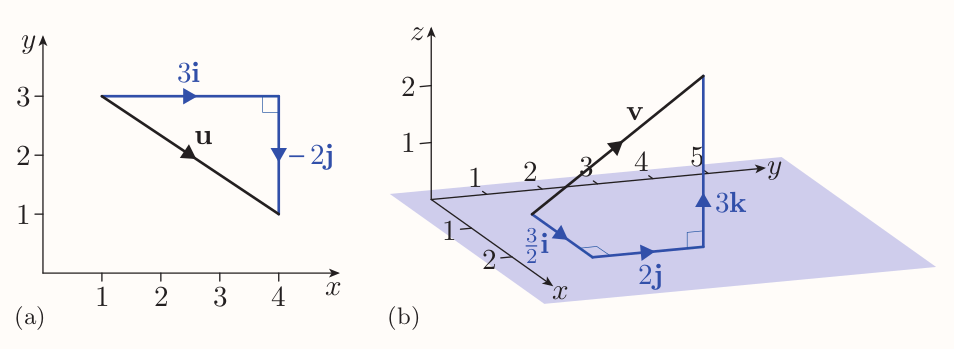

Components are vectors in the directions of the $x$-, $y$- and $z$-axes with magnitude 1. These vectors are denoted by $\textbf{i}$, $\textbf{j}$ and $\textbf{k}$ respectively, and are called the Cartesian unit vectors.

Any vector can be expressed as sums of scalar multiples of the Cartesian unit vectors

Component form of a vector

If $\textbf{v} = a\textbf{i} + b\textbf{j}$, then the expression $a\textbf{i} + b\textbf{j}$ is called the component form of $\textbf{v}$. The scalars $a$ and $b$ are called the $\textbf{i}$-component and $\textbf{j}$-component, respectively, of $\textbf{v}$.

Similarly, if $\textbf{v} = a\textbf{i} + b\textbf{j} + c\textbf{k}$, then the expression $a\textbf{i} + b\textbf{j} + c\textbf{k}$ is called the component form of $\textbf{v}$. The scalars $a$, $b$ and $c$ are called the $\textbf{i}$-component, $\textbf{j}$-component and $\textbf{k}$-component, respectively, of $\textbf{v}$.

Alternative component form of a vector

The vector $a\textbf{i} + b\textbf{j}$ can be written as $\begin{pmatrix}a \ b \end{pmatrix}$.

The vector $a\textbf{i} + b\textbf{j} + c\textbf{k}$ can be written as $\begin{pmatrix}a \ b \ c \end{pmatrix}$.

A vector written in this form is called a column vector.

For example, $$ 4\textbf{i} - 3\textbf{j} = \begin{pmatrix} 4 \ -3 \end{pmatrix} $$

Also, $$ \textbf{i} = \begin{pmatrix}1 \ 0 \ 0\end{pmatrix}~,~~~ \textbf{j} = \begin{pmatrix}0 \ 1 \ 0\end{pmatrix}~,~~~ \textbf{k} = \begin{pmatrix}0 \ 0 \ 1\end{pmatrix} $$ And $$ \textbf{0} = 0\textbf{i} + 0\textbf{j} + 0\textbf{k} = \begin{pmatrix}0 \ 0 \ 0\end{pmatrix} $$

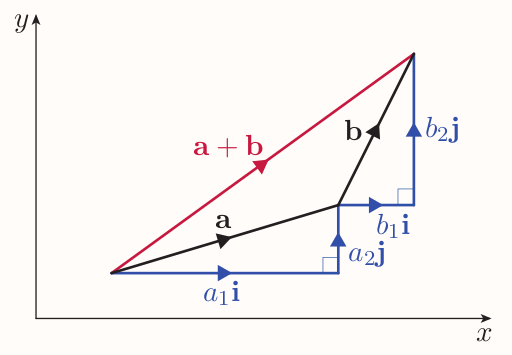

Sometimes its useful to denote the components of a vector by same letter: $$ \textbf{a} = a_1\textbf{i} + a_2\textbf{j} = \begin{pmatrix}a_1 \ a_2\end{pmatrix} $$

6.2 Vector algebra using components

If $\textbf{a} = a_1\textbf{i} + a_2\textbf{j}$ and $\textbf{b} = b_1\textbf{i} + b_2\textbf{j}$, then $$ \begin{align} \textbf{a} + \textbf{b} &= a_1\textbf{i} + a_2\textbf{j} + b_1\textbf{i} + b_2\textbf{j} \ &= (a_1 + b_1)\textbf{i} + (a_2 + b_2)\textbf{j} \end{align} $$

Hence, to add two two-dimensional vectors, their corresponding components should be added.

Addition of two-dimensional vectors in component form

If $\textbf{a} = a_1\textbf{i} + a_2\textbf{j}$ and $\textbf{b} = b_1\textbf{i} + b_2\textbf{j}$, then $$ \begin{align} \textbf{a} + \textbf{b} &= (a_1 + b_1)\textbf{i} + (a_2 + b_2)\textbf{j} \end{align} $$ In column notation, if $\textbf{a} = \begin{pmatrix}a_1 \ a_2\end{pmatrix}$ and $\textbf{b} = \begin{pmatrix}b_1 \ b_2\end{pmatrix}$, then $\textbf{a} + \textbf{b} = \begin{pmatrix}a_1 + b_1 \ a_2 + b_2\end{pmatrix}$

Vectors in three dimensions are added in similar way.

This fact extends to sums of more than two vectors.

Negative of a vector in component form

If $\textbf{b} = b_1\textbf{i} + b_2\textbf{j} + b_3\textbf{k}$, then $-\textbf{b} = -b_1\textbf{i} - b_2\textbf{j} - b_3\textbf{k}$. In column notation, if $\textbf{b} = \begin{pmatrix}b_1 \ b_2 \ b_3\end{pmatrix}$, then $-\textbf{b} = \begin{pmatrix}-b_1 \ -b_2 \ -b_3\end{pmatrix}$

Subtraction of vectors in component form

If $\textbf{a} = a_1\textbf{i} + a_2\textbf{i} + a_3\textbf{k}$ and $\textbf{b} = b_1\textbf{i} + b_2\textbf{i} + b_3\textbf{k}$, then $$ \textbf{a} - \textbf{b} = (a_1 - b_1)\textbf{i} + (a_2 - b_2)\textbf{j} + (a_3 - b_3)\textbf{k} $$ In column notation, if $\textbf{a} = \begin{pmatrix}a_1 \ a_2 \ a_2\end{pmatrix}$ and $\textbf{b} = \begin{pmatrix}b_1 \ b_2 \ b_3\end{pmatrix}$, then $\textbf{a} - \textbf{b} = \begin{pmatrix}a_1 - b_1 \ a_2 - b_2 \ a_3 - b_3\end{pmatrix}$

Multiplication of vectors by scalars

If $\textbf{a} = a_1\textbf{i} + a_2\textbf{j}$ and $m$ is scalar, then $$ \begin{align*} m\textbf{a} &= m(a_1\textbf{i} + a_2\textbf{j}) \\ &= ma_1\textbf{i} + ma_2\textbf{j} \end{align*} $$

Scalar multiplication in component form

If $\textbf{a} = a_1\textbf{i} + a_2\textbf{j} + a_3\textbf{k}$ and $m$ is a scalar, then $m\textbf{a} = ma_1\textbf{i} + ma_2\textbf{j} + ma_3\textbf{k}$. In column notation, if $\textbf{a} = \begin{pmatrix}a_1 \ a_2 \ a_3\end{pmatrix}$, then $m\textbf{a} = \begin{pmatrix}ma_1 \ ma_2 \ ma_3\end{pmatrix}$.

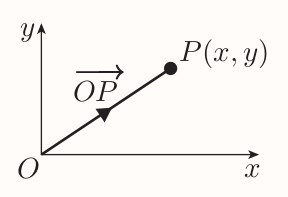

6.3 Position vectors

Position vector of a point $P$ is the displacement vector $\vec{OP}$, where $O$ is the origin.

The position vector of the point $P(x, y)$ is $$ \vec{OP} = x\textbf{i} + y\textbf{j} = \begin{pmatrix}x \ y\end{pmatrix} $$

Any displacement vector $\vec{AB}$ can be expressed in terms of the position vectors of the points $A$ and $B$.

Since $$ \vec{AB} = \vec{AO} + \vec{OB} $$ it follows that $$ \vec{AB} = -\vec{OA} + \vec{OB} $$ that is $$ \vec{AB} = \vec{OB} - \vec{OA} $$ Hence following definition

If the points $A$ and $B$ have position vectors $\textbf{a}$ and $\textbf{b}$, respectively, then $$ \vec{AB} = \textbf{b} - \textbf{a} $$

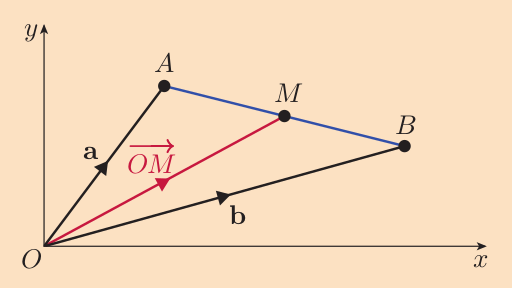

Alternative proof of the midpoint formula

Consider $A(x_1, y_1)$, $B(x_2, y_2)$. Let $M$ be the midpoint of $AB$, let $\textbf{a}$, $\textbf{b}$ and $\textbf{m}$ be the position vectors of $A$, $B$ and $M$, respectively.

$$ \vec{OM} = \vec{OA} + \vec{AM} $$

that is, $$ \textbf{m} = \textbf{a} + \vec{AM} $$ $\vec{AM}$ has the same direction as $\vec{AB}$ but half its magnitude, so $$ \vec{AM} = \frac{1}{2}\vec{AB} = \frac{1}{2}(\textbf{b} - \textbf{a}) $$ hence $$ \begin{align*} \textbf{m} &= \textbf{a} + \frac{1}{2}(\textbf{b} - \textbf{a}) \\ &= \textbf{a} + \frac{1}{2}\textbf{b} - \frac{1}{2}\textbf{a} \\ &= \frac{1}{2}\textbf{a} + \frac{1}{2}\textbf{b} \\ &= \frac{1}{2}(\textbf{a} + \textbf{b}) \end{align*} $$

Since $\textbf{a} = x_1\textbf{i} + y_1\textbf{j}$ and $\textbf{b} = x_2\textbf{i} + y_2\textbf{j}$, then $$ \begin{align*} \textbf{m} &= \frac{1}{2}(x_1\textbf{i} + y_1\textbf{j} + x_2\textbf{i} + y_2\textbf{j}) \\ &= (\frac{x_1 + x_2}{2})\textbf{i} + (\frac{y_1 + y_2}{2})\textbf{j} \end{align*} $$

Giving following definition

Midpoint formula in terms of position vectors

If the points $A$ and $B$ have position vectors $\textbf{a}$ and $\textbf{b}$, respectively, then the midpoint of the line segment $AB$ has position vector of $\frac{1}{2}(\textbf{a} + \textbf{b})$.

6.4 Converting from component form to magnitude and direction, and vice versa

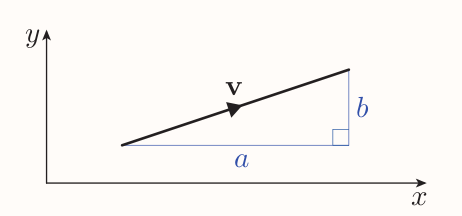

Finding the magnitude of a vector from its components

In

$a$ and $b$ are the magnitudes of the components of $\textbf{v}$.

$a$ and $b$ are the magnitudes of the components of $\textbf{v}$.

By Pythagoras' theorem, the magnitude of the vector $\textbf{v}$ is given by $$ |\textbf{v}| = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2} $$

This formula holds for any vector $\textbf{v} = a\textbf{i} + b\textbf{j}$. Hence

The magnitude of a vector in terms of its components

The magnitude of the vector $a\textbf{i} + b\textbf{j} + c\textbf{k} = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2 + c^2}$

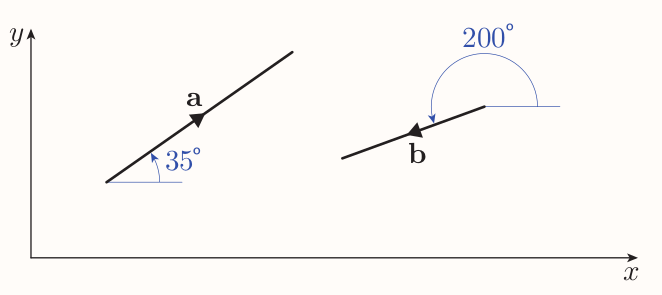

Finding the direction of a two dimensional vector from its components

Another method to specify the direction of a two-dimensional vector besides bearing is to state the angle measured from the positive $x$-direction to the direction of the vector anticlockwise.

Suppose a vector in component form and unknown angle against some reference direction, then the right-angled triangle can be sketched with the vector as hypotenuse. Then basic trigonometry can be used to find the acute angle that can be used to find the desired angle.

Finding the components of a two-dimensional vector from its magnitude

- Sketch the right-angled triangle whose hypotenuse is the vector

- Use basic trigonometry to find the magnitudes of the components

- Using the direction of the vector find their signs

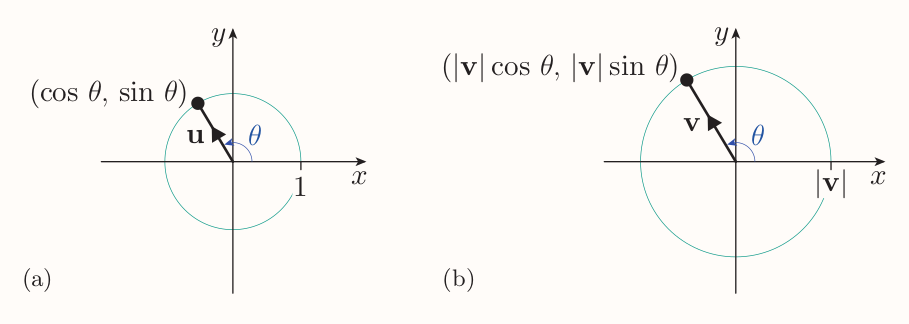

Consider a vector $\textbf{v}$ that makes the angle $\theta$ with the positive $x$-direction. Let $\textbf{u}$ be the vector in same direction but with magnitude 1. When placed on origin, its tip lies on unit circle, hence it has coordinates of $(\cos\theta, \sin\theta)$. Hence $$ \begin{align*} \textbf{u} &= \cos\theta\textbf{i} + \sin\theta\textbf{j} \\ \text{v} &= |\textbf{v}|(\cos\theta\textbf{i} + \sin\theta\textbf{j}) = |\textbf{v}|\cos\theta\textbf{i} + |\textbf{v}|\sin\theta\textbf{j} \end{align*} $$

So following fact

Component form of a two-dimensional vector in terms of its magnitude and its angle with the positive $x$-direction

If the two-dimensional vector $\textbf{v}$ makes the angle $\theta$ with the positive $x$-direction, then $$ \textbf{v} = |\textbf{v}|\cos\theta\textbf{i} + |\textbf{v}|\sin\theta\textbf{j} $$

7 Scalar product of two vectors

Is a way to multiply two vectors, also known as the dot product. It provides a convenient method for finding the angle between any two vectors.

7.1 Calculating scalar products

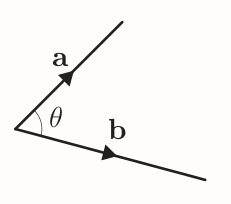

The angle between two vectors $\textbf{a}$ and $\textbf{b}$ is the angle $\theta$ in the range $0 \le \theta \le 180^{\circ}$.

Scalar product of two vectors

The scalar product of the non-zero vectors $\textbf{a}$ and $\textbf{b}$ is $$ \textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{b} = |\textbf{a}| |\textbf{b}|\cos\theta $$ where $\theta$ is the angle between $\textbf{a}$ and $\textbf{b}$.

If $\textbf{a}$ or $\textbf{b}$ is the zero vector, then $\textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{b} = 0$.

The scalar product is scalar because none of the quantities has a direction.

If two non-zero vectors are perpendicular, then their scalar product is zero since $$ \textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{b} = |\textbf{a}| |\textbf{b}|\cos90^{\circ} = |\textbf{a}| |\textbf{b}|\times0 $$

The scalar product of a vector with itself is equal to the square of the magnitude of the vector since $$ \textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{a} = |\textbf{a}||\textbf{a}|\cos0^\circ = |\textbf{a}||\textbf{a}| \times 1 = |\textbf{a}|^2 $$

Properties of the scalar product

The following properties hold for all vectors $\textbf{a}$, $\textbf{b}$ and $\textbf{c}$, and every scalar $m$.

- Suppose that $\textbf{a}$ and $\textbf{b}$ are non-zero. If $\textbf{a}$ and $\textbf{b}$ are perpendicular, then $\textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{b} = 0$, and vice versa.

- $\textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{a} = |\textbf{a}|^2$

- $\textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{b} = \textbf{b} \cdot \textbf{a}$

- Operation of taking scalar product is commutative

- $\textbf{a} \cdot (\textbf{b} + \textbf{c}) = \textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{b} + \textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{c}$

- Operation of taking scalar product is distributive over vector addition

- $(m\textbf{a}) \cdot \textbf{b} = m(\textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{b}) = \textbf{a} \cdot (m\textbf{b})$

- Multiplication by a scalar is distributive over the operation of taking a scalar product

Calculating scalar products from components

Consider $\textbf{a} = a_1\textbf{i} + a_2\textbf{j}$ and $\textbf{b} = b_1\textbf{i} + b_2\textbf{j}$ Their scalar product is $$ \begin{align*} \textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{b} &= (a_1\textbf{i} + a_2\textbf{j}) \cdot (b_1\textbf{i} + b_2\textbf{j}) \\ &= (a_1\textbf{i}) \cdot (b_1\textbf{i}) + (a_1\textbf{i}) \cdot (b_2\textbf{j}) + (a_2\textbf{j}) \cdot (b_1\textbf{i}) +(a_2\textbf{j}) \cdot (b_2\textbf{j}) \\ &= a_1b_1(\textbf{i} \cdot \textbf{i}) + a_1b_2(\textbf{i} \cdot \textbf{j}) + a_2b_1(\textbf{j} \cdot \textbf{i}) + a_2b_2(\textbf{j} \cdot \textbf{j}) \end{align*} $$

Given the properties of the scalar product and the fact both $\textbf{i}$ and $\textbf{j}$ have magnitude 1, we get following definition

Scalar product of vectors in terms of components

If $\textbf{a} = a_1\textbf{i} + a_2\textbf{j} + a_3\textbf{k}$ and $\textbf{b} = b_1\textbf{i} + b_2\textbf{j} + b_3\textbf{k}$, then $$ \textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{b} = a_1b_1 + a_2b_2 + a_3b_3 $$

In column notation, if $\textbf{a} = \begin{pmatrix}a_1 \ a_2 \ a_3\end{pmatrix}$ and $\textbf{b} = \begin{pmatrix}b_1 \ b_2 \ b_3\end{pmatrix}$, then $\textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{b} = a_1b_1 + a_2b_2 + a_3b_3$

7.2 Finding the angle between two vectors

Rearranging the definition of the scalar product gives following fact

Angle between two vectors

The angle $\theta$ between any two non-zero vectors $\textbf{a}$ and $\textbf{b}$ is given by $$ \cos\theta = \frac{\textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{b}}{|\textbf{a}||\textbf{b}|} $$